Welcome to my Substack #15. This stacked prose piece was inspired by an interview I gave to the The Met’s Immaterial Podcast on the theme of “paper”. Soundtrack: Paper Paper Playlist

1. The most perfect paper ephemera has a certain rough texture to it, so that when you rub it between your fingers, you think you might rub a hole and a little residue comes off on your fingers. It feels thin – not as fragile as tissue paper but not as thick and stiff as the heavy weight paper you find in the photocopy machine of your local printers. The paper ephemera I am drawn to are the paper ephemera meant to disintegrate quick – the old train ticket used when trekking across India and casually thrown to the floor, yellowed envelopes sending long distant love letters, old newspaper used to wrap precious glass or ceramics. The more textured the paper, the more fall apart quality, the better. Paper that is so inconsequential that they didn’t bother to bleach it and the ink printed on the paper would bleed on the edges of the text. The more it is meant to not exist, the better it is to save. It is a death cycle of an obsession I’ve entered in.

2. e·phem·er·a: /əˈfem(ə)rə/ – “items of collectible memorabilia, typically written or printed ones, that were originally expected to have only short-term usefulness or popularity.”

3. I would keep boxes and boxes of paper ephemera before I knew what ephemera was – I would call them “Memory Boxes” full of little trinkets and papers of things that happened that I would want to remember. After one shoe box was full of pebbles, concert tickets, passed notes, I would put it in the closet and start a new one. I would look through these boxes every few years – culling out the memories I no longer remembered and re-reminding myself what once was. It was like reading an old journal but tactile.

4. Collaging with modern day paper doesn’t feel right. The glue doesn’t sink into the paper, and after it dries, it leaves a shiny gloss atop of the paper. The perfect old paper absorbs the ink of gouache paint with a brightness and sticks to canvass with a tightness. You can layer and glue and paint and glue again without having to worry about the seamlessness of it all.

5. I used to call my mother a hoarder but after she died and we cleaned out her closet, we realized she didn’t actually have that much significant stuff. Her hoard was just clutter but her saved stuff was carefully curated. Which made sense because we moved around so much the first 15 years of her life in the U.S. – it just cost money to move things from house to house, so if you kept it, it better be worth it. As we went through her things, we noted how what was saved were specific collections of preciousness. Empty perfume bottles on a mirrored tray. Dusty saris permanently creased on hangers. Plastic Avon jewelry in Kmart jewelry boxes. In the back of her drawer a muslin bag of all the international stamps she ever collected as a teen. A Tupperware box of every greeting card that was ever exchanged in this family. Another Tupperware of tightly packed pale blue aerogram letters, all in the Bangla handwriting of my Nani and Nana. My mother’s ephemera.

6. The week after mom died, I was sadly folding paper airplanes with scraps and throwing them through the air as we sat around and mourned. I had found the aerogram letters and I wanted to honor it through art – and paper airplanes seemed like the perfect symbolism. I poured over the letters reading the English words and looking to make sure I wasn’t destroying anything I wasn’t supposed to be. The words I could read just talked about t.v. shows and asking why the letters had become infrequent. When I finally had my first solo art show in Oakland, I was so conflicted with knowing that my art made from my mother’s paper ephemera was being sold into strange hands. I priced the pieces outrageously so they wouldn’t sell and privately sold to friends after the show ended. Some people suggested I make photocopies – but the quality of the pieces looked so inauthentic when I glued it to the canvass. The thickness and the texture of the Kinkos paper quality was the tell. Paper ephemera art can’t be photocopied. What is the point, even?

7. Under the street lamp on a dark road in Frogtown, we all hugged goodbye. We started to walk away when Randa called over to us to see if we wanted books. She popped her trunk. She was moving, and her trunk was full of books from her move. Of course we wanted books that were curated by Randa’s hands and in her trunk. It was like buying bootleg purses by a purse maker from the trunk of a car on shady streets, except, books, and it wasn’t illicit. She grabbed a book out of my hand and throws it in the gutter – you can’t have that book, no one can. I hate them, let the streets have them, she said. I asked for a book with Arabic and thin paper. Into her trunk she reached and picked up a book in Arabic, but feels the pages and said it wasn’t the texture I like. That’s a real friend right there – one who knows what texture of paper you crave. After digging around, she found me an Egyptian book on torture practices on thin textured pages and tiny Arabic font, which for my art, is perfect.

8. The first place I would check when as a kid we would go to my Nani and Nana’s house in Bangladesh was the dresser in the upstairs living room. Cracking open the top drawer carefully, heavy with paper, I would sniff deep. It was the distinct smell of sacred books in a moist environment and moth balls. Stuffy, moldy, stale. It seemed like it was always raining in Dhaka, and even when it wasn’t raining, the humidity would just hang in the air. Inside this drawer was my refuge, and where I would lose myself those summer months – into the lives of Enid Bylton’s Famous Five (Georgina was my favorite), The Adventures of Tin Tin, and dog-eared copies of Archies. They had belonged to my aunt as a kid, stored away for safekeeping. When I had carefully read through everything I could get my hands on, I asked for my mother’s childhood books. They had to leave them behind, she said. But why wouldn’t they let you bring your precious books, I asked astonished. We had 24 hours to leave and we had to carry everything we could to get out of Lahore and back to Bangladesh, she said. Then what did you do with your books, I asked, still astonished. We left them with family friends to save for us, and we never got them back, she said. The ephemera of the leaving behind books in a civil war.

9. sil·ver·fish: /ˈsilvərˌfiSH/ a chiefly nocturnal silvery bristletail that frequents houses and other buildings, feeding on starchy materials.

10. The silverfish looked nothing like a fish, but like a silver flat many legged centipede. They haunted the corners of the paper drawers and skittered out when I would open a book at my Nana’s house. The books with have tell-tale signs of yellowed pages, gnawed edges and fragile holes, whole paragraphs of narrative I would have to fill with my imagination.

11. It’s such a luxury to be able to be so cavalier with paper. No dehumidifier, no moth balls, no silverfish, no gloves, no need for preciousness of paper. This Californian desert air is such an extravagance.

12. My first “job” was volunteering at the local library. It was, in retrospect, a free babysitter for my mother and something to keep me busy during my early teen years. She would drop me off at the library during summer days where I would spend hours and hours stocking shelves in Dewey decimal order. I loved rifling through the pages and finding books I wanted to read before everyone else could. It was cool in the library, with the air conditioning on blast and it just smelled of clean dry Californian books. It was safe.

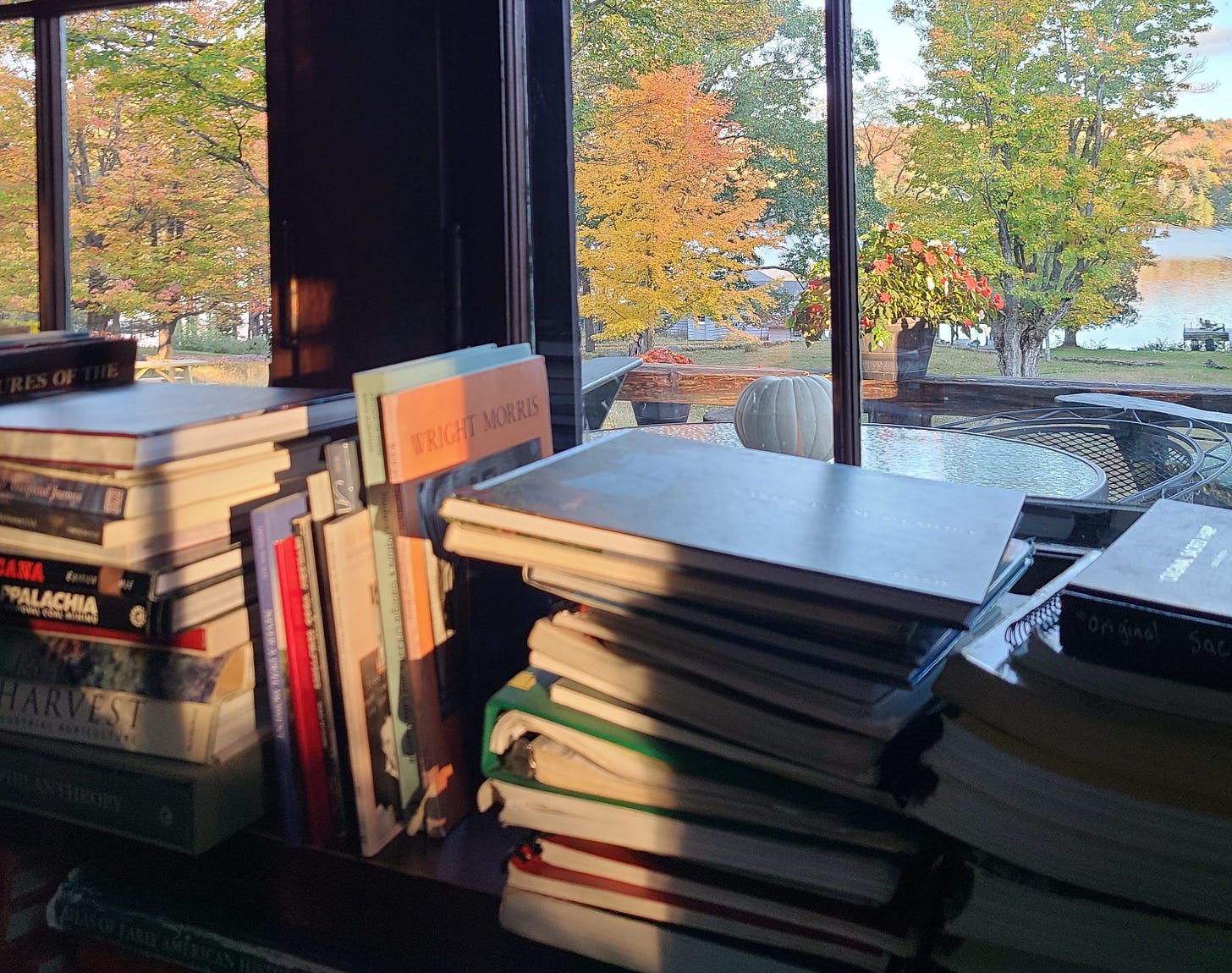

13. Back in October, the first night I arrived to the residency in the Adirondacks I couldn’t sleep. My bedroom was in the former dining room of the gray lake house, with a view of trees rapidly changing colors of fall outside my picture window. Along one side of the wall there were hundreds of books, in no particular order. How was I supposed to sleep with a whole wall of unorganized books in my room? That night, I knew I wouldn’t be able to sleep until I organized the books on the shelves – first pulling out all the books I wanted to read, then pulling out the ones that were thematically orientalist, then shelving the hard cover old books to the top of the shelf, and the newer books to the bottom, in thematic order, then by color, then by size. Even after all that I couldn’t fall asleep from the mustiness from the old books. I slept much better the rest of the month after the turned on a humidifier in the room.

14. Before the mid-19th century, paper in the Western world was made from shredded cotton and linen rags. These cotton pages would remain durable over time because the fibers were longer – preserving words over thousands of years. After the mid-19th century, mechanically pulped wood became the source of paper – and more acidic – making it deteriorate at a faster rate. This is why paper from hundreds of years ago is more likely to be preserved than paper from just a few decades ago.

15. When we make art – how long do we want it to last for? How precious is what we are making? I go through the extra steps of spraying my art with UV protecting varnish and using expensive non-yellowing collage paste and even more expensive archival ink. But I don’t need my art to last forever, or even 100 years, I don’t think. My art uses ephemera but maybe my art also is ephemera, and in that case, the deterioration of my art, the ephemera of it, means maybe I too shouldn’t have this kind of preciousness. Maybe, if the ephemera bad quality paper I glue in my art deteriorates at a fast rate, maybe that is okay and just part of this process. I’m deeply inspired by the Noah Purifoy exhibit in Joshua Tree, and how he left his art outside in the desert to be deteriorated by the weather elements. I make it a point to visit every time I go to the desert and I’m always in awe of how in the deterioration, there are always new elements of discovery. It’s the most tangible example of time pass. Maybe if he can let his art turns into dust, then I don’t need my art to be forever, either.

16. When people ask me what they can bring back for me from the motherland, I ask for old paper with Bangla language on from before the 80s. I tell them to find old used book stores and rummage through the racks, but they all return empty handed. It is a practiced skill, after all, I know. I have run out of my own paper ephemera, having used up all the scraps of paper with texture in every memory box and bookshelf. We have no Bangla text books at my dad’s house, except for the errant Tagore song book which is far too precious to cut. I refuse to cut up the aerogram letters anymore, at least not yet. On the internet I search for Bangla script on old textured paper on Etsy and Ebay and Poshmark. The algorithms autocorrect Bangles for Bangla, because technology can be racist too. I find a shop in Jaipur that sends me old Urdu text books about Sufi saints and pages of receipt books in Urdu. It makes sense if you know history, how Urdu was used as a language of oppression – Bangladeshis fought for the right to have Bangla recognized. On Feb 21st, 1952 five people died and hundreds injured at a protest for the right to have Bangla recognized as a national language. Twenty year later, Bangladesh would gain independence. So of course, in a civil war of based in language of course it is almost impossible to find Bangla text paper. Of course, the oppressors Urdu language papers were preserved. Of course.

17. People tell me they want to buy my art pieces with my precious ephemera. It is not for sale, I respond offended. Why do hobbies have to be turned into commerce, why does art making need to be a part of product capitalism? These paintings were made with MY ephemera - my ticket for a solo train ride to Bangalore, my Nani’s handwriting in an blue aerogram, my mother stamp collection. I will make you a custom commission using your paper ephemera, I decided to respond with, I just ask that it be in-language and old. Afterall, I wasn’t offended by being asked for my art, but that I couldn’t part with my precious ephemera. People send me pages of calendars, old comic books, old pages from childhood textbooks, wedding invitations, old poetry and I make so many paintings using others ephemeras. I feel honored. The preciousness is collective.

18. My strategy at vintage stores is to do a quick sweep with my eyes to see if there is anything remotely orientalist on the wall or a section of books. If there is one orientalist mask on the wall or camel ashtray on the table, there is usually more in that section. In the book area, I will look for paper that has yellowed or book binds that are hard covered and tattered. I look for book titles that say “palm” or “jungle” or “Mecca”, and for images of palm trees or tigers or genie lamps or Persian carpets. Pulp erotica books are the best finds, but more often than not, it’s young adult book written by a white name where the protagonist finds themselves on a journey through the orient. I ask myself, will I feel guilty if I cut up the pages of this book for my art? Is this topic relevant enough that pages will mean something in the subject of my art? Will making this book into art decolonize or tokenize?

19. Whatever paper ephemera I have amassed so far is still just not right.

20. I dream of going back to the motherland for scavenging trips for paper ephemera when this pandemic ends. Like every other post-college Brown kid in their 20s in the 2000s, I also went backpacking in South Asian. Bookstores were around, but the best books were the cheap knockoffs that you’d find being sold on the sidewalk by bootleg vendors. Who would bootleg a book, I wondered back then. The quality was cheap, the book cover obviously a photograph. I would buy a bootleg book here and there, but never brought them back home. I would return from these trips to India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka with fashion magazine of Desi brown skinned models or rip out one page of the singles ad in the back of a newspaper. My valuable suitcase space was reserved for saris, tailored blouses and homemade guava jam. If I could go back, I’d wander through the allies of Old Dhaka, Old Delhi, and Old Kathmandu looking for ephemera to use in my art – rickshaw art that I can cut and collage; old letters from the USA sent to the motherland; yellowed matchmaking ads and astrology pages in newspapers. I would look again in my grandparents storage to see if any paper ephemera was left that my mom touched, or saris that could be ripped up and collaged.

21. I dream in paper and nostalgia. The making of future ephemera.

Such a beautiful piece! Thank you for writing it