Like Watching Paint Dry

A (long) meditative reflection on my first Los Angeles solo art show.

Welcome to my Substack #24. Soundtrack for this post: Writing in Saguaros

1. Have you ever watched paint dry? It is incredibly dulling, like watching a hot kettle waiting for the whistle or sitting in Friday afternoon traffic in Southern California. There is an urgency, because once the paint is dried, you can move on to the next layer, next steps for the final vision. But it can’t be rushed because you run the risk of smudging paint with your palm or wet colors melding into each other or an unfixable mess. You have to wait. You are forced to wait. While you watch the paint dry, it will give you signs, first by mattifying in color, on the edges then towards the middle. Unless you used a lot of water for a translucent effect – then the changes are so subtle, you look for a sheen or a reflection or something to tell you when you tap it with your finger, a fingerprint won’t be left behind. Oil paint stays wet forever and watercolor dries very quickly – but my preferred medium of acrylic gouache on wood, and that cannot be rushed. The thinner the layer, the faster the dry. But that also means, having to add more layers to get the color you want, which takes up more time. And do we have the time to watch the paint dry? Can we time manage to work on three pieces at the same time to always have a piece drying? And sometimes, there is absolutely no point to asking questions on efficiency because the paint, glue, gesso, and varnish will dry when they want to and you just have to pause along.

2. "Like watching paint dry" is an English-language idiom describing an activity as being particularly boring or tedious. It is believed to have originated in the United States. A similar phrase is "watching the grass grow". Wikipedia

3. The first layer to all the paintings is a wash of background color, preferably pink. Technically though, when working with wood, it’s the clear gesso layer that protects the paint from leaking through to the porous wood. But, when working with an ink transfer, it’s technically the printed photo laid face forward on a thick layer of glue, which, 24 hours later, you dribble with water and with your fingers you rub the paper off in spools and you are left with your image on the wood. Unless, of course, you are collaging, and then the first layer is digging through your paper ephemera boxes and old books and finding key texts and image that would make a good secret story in your painting. And in that case, the first layer is staring into space, painting in your daydreams.

4. “You just have to paint faster,” someone said, when I complained about how I didn’t have enough time to finish all the pieces I wanted to finish for my solo art show. I had wanted 24 pieces, but after visiting the gallery, I was overwhelmed by the how big the white walls. “But I have to wait for the paint to dry,” I responded. You can’t speed air. There are certain things you can speed, when it comes to productivity. Take writing. My best writing for my column came when I was writing the night before the looming deadline. You can, technically, write fast, speed read, eat quick, drive swift. But a painting drying is constrained by the invisible outside force of the speed of evaporation in the air. There is no control. You just have to give.

5. The deliberation room for jury duty had these horizontal blinds that looked down upon Los Angeles’ City Hall where the California sun snuck in sideways. Almost all of us jurists agreed that the man was in possession of a shank in the prison cell, and both smarmy weak-jawed lawyers didn’t give us reason to believe otherwise. Under oath, the guard on duty who found the shank asked the defendant if it was his and he had responded yes, and that he used it to fix shoes. You don’t need to be a cobbler to know that it was a lie. Even then, the old Korean Uncle with the slight stutter and the graying hair said, he didn’t believe that the shank belonged to him. He wondered out loud to the quiet deliberation room if it was planted by a guard. All the jurists around the table gently tried to tell him that of all the points presented, that wasn’t the one we were debating over – but he was stubbornly in-convincible. Abruptly, the conversation around the table stopped. It was dead silence. I stared out the window wondering if this idiotic case was going to result in a hung jury. I stared out the window for an hour, or maybe two. I came back the next day and stared out the window some more. All I could think about was how I should be making more art, and that this time could have been used making more art and what an idiotic reason it was for us to be in trial. That next day, the stenographer came into the room and read the transcript from the trial where the guard said the defendant said it was his. That was enough to change the Korean Uncle’s mind, and finally, we went home.

6. Sometimes you just have to let the time pass, because you have no control.

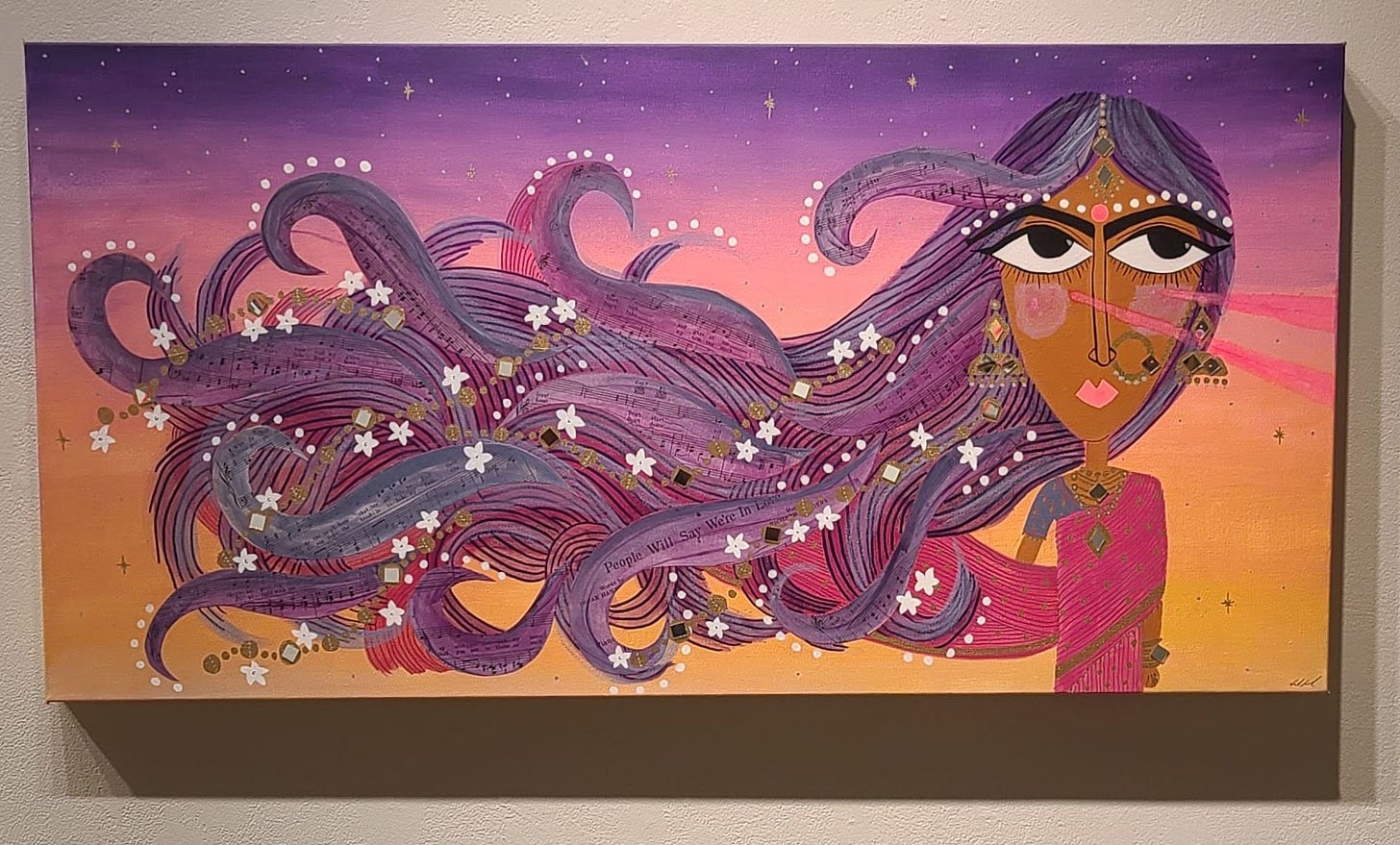

7. After the background has dried, the second layer is the gluing of the paper to the canvas. It has to be done thinly and precisely, so as to make it seamless. It has to be done with pricey archival glue because I learned too late the yellowing property of cheap glue. Which brings up the awkward existential crisis of what is the lifetime of the art that we are making for? Is it for ourselves or for others? In a hundred years, will this be in the LACMA archives or in my mythical grandchildren’s attics? Are my old sold pieces sitting in garages, already? Once the paper is applied, you have to smooth it out carefully with a hard edge to prevent bubbling, and gentle enough to prevent tearing. If you add too much glue it will harden thick and look amateurish like a child’s mod-podged artwork for the fridge. Thinly applied, it is almost imperceptible, and the cut-out paper looks like it was always meant to be. And then, of course, you have to wait for it to dry.

8. There is this limbo period between when someone dies and someone is buried. In Islam, that time period is truncated – a body is expected to be buried as soon as possible, barely enough time to book the next flight out. I texted the Gallerist that I wouldn’t be able to install my art the Sunday before the art show like I had planned. I had to drive to Santa Ana Airport on a Friday afternoon to catch the cheapest flight to Dallas for a janaza. Flying into this grief is like being on The Langoliers plane and flying into a place where time has no movement. The inciting incident has already happened and you are there to help with picking up the pieces of whatever you can help with. Putting away food. Wiping away tears. Listening to the processing. Clicking prayers on thosbee beads. Throwing rose petals in the lake where he spent his last days. What is grief but the location where time stand stills the longest and goes by the quickest. You are forced to just be present in your body, being reminded you still have a body. What a gift being alive is, what a tortured existence life can be. Sitting in sadness. I can’t remember enough to tell you all of what we did in Dallas, but I remember that the Texas skies were still wide and blue, the mockingbird trilling songs loudly at the graveyard, the fireworks on the horizon, the crackle of the summer lightening storm, and the feeling that he was finally at peace.

9. The next layer, after the drawing of the object, is the painting of the skin. Brown skin, like mine, sometimes darker, sometimes lighter, but always something like mine. Because when your walk through the Getty, or the LACMA, or the MOCA, it’s never Brown skin like mine that you see. A squirt of Raw Sienna mixed with Portrait Pink or Peach or Mustard Yellow with a small squeeze of Parchment. Then I paint the hair in waves or in braids, opaque or translucent. And then the almond shaped whites of the eyes. And then a watery pink blush with cotton balls. And only then with a Posco acrylic paint pen do I carefully draw the repetitive lines of the strands of the hair.

10. I have vertigo the day we have to install, I attribute it to my dehydration from my middle-aged sensitive tummy. I call Neela in panic, and she comes over to help me take my art to the gallery. I don’t feel sick-sick, but I am forced to go slow, deliberate. My inclination to be time efficient is stifled by my body. We take the paintings and place them around the gallery on the floor leaning them on the wall. The night before the opening, it’s just the Gallerist and I in the gallery, and a lot of bare white walls. He takes his time, asking thoughtful questions and a deliberate patience with reverence for the art, my art. He has done this for the past fifteen years, yet still his pause makes me take pause. My inclination is to play punk music and to tornado through the gallery making rash decisions and install as fast as possible. It is likely related to my inclination to take up less time and make myself small, accommodating. But the Gallerist’s slowness forces me to slow down and take a beat in this process. He’s in no rush because he wants things to be perfect. We take fifteen minutes to discuss how to drape the floor length canvas of eyes, and have a long conversation on how we want people to experience a story when walking through the gallery. I apologize profusely before asking him to move a painting three inches to the left. He tells me not to apologize and whatever I want we can do. In this space, I realize, this was the end goal of making all this art. And if this was the end goal, why should I rush it? It’s to be savored, every moment of it. I am forced, again, to take my time.

11. The white space between the paintings on the wall is like a visual pause. “Don’t feel the need to fill up all the space with paintings,” Adnan told me, when I had asked him for solo art show advice. “You have to give space for the paintings to breath, and for your audience to breath.” The bare walls between each piece were a visual pause, an artistic paragraph break, forced ellipses. After the paintings were on the wall, I could see what he meant.

12. I paint the eyeliner like I do my own eyes. From the outside in, making the wings wide and sharp. I make tiny triangles on the corner of the eyes like I do my own. Carefully, I trace the edged of the whites as if painting kajol on waterlines are in my ancestral DNA. Next, are the pupils of the eyes, half disks the way Jamini Roy does. And then I paint the lush fan of lower lashes, with a Maybeline flair. Using the black waterproof eyeliner was just circumstantial to painting in the pandemic – it was the only sharp tipped black felt tip I had when the world shut down. I kept using it because it was the only paint medium that didn’t crack while drying.

13. The hospital waiting room is the uneasiest. It’s different than the timepass of waiting for a surgery to finish and the conclusion text that the surgery went as planned. That has a conclusion. The text letting us know that Khala is back in the emergency room are weekly – her heart keeps beating too fast. She stays in the hospital room as we all just wait – for the medicine to work, for the doctors to visit, to see if her body changes. It’s the timepass of waiting for a body to heal, to see if the medicine takes, and seeing if her body will heal some more. Watching the monitor and waiting. Sitting and waiting. I’m in Palm Springs, the day after we take down the art, when I get the text that she is not doing well. She needs major surgeries and risky procedures. When I’m finally allowed to visit her at the hospital, I show her pictures of the art show on my phone. She seems distracted. Then, Khala sits quietly as my sister tenderly brushes her tangled hair and twists it into a long French braid. I tear up from the intimacy. And then she dozes off, while we sit on the sofa in her room, and wait for the healing some more.

14. The adornment layer is my favorite part. It reminds me of the ritual of adorning my own body before parties. Taking the delicious moment to dig through old jewelry boxes and find the longest jhumkas or biggests naaths to wear. The Desi-Femme-ness of it all, is so exhilarating. With silver and gold Krylon paint pens, I adorn. I paint tear dropped tiklis. The tiny bells on half circle jhumkas. Dangles of diamonds from the neck. Drapes of chains from nose to ear. I adorn.

15. Being an artist is an incredibly lonely experience. With writing, I’ve figured out how to co-write with other people at cafes and over zooms to make it less lonely. But you can’t take a 30”x40” canvas to work on at a coffee shop with the same ease. Writing forces me to reflect, to take the jumble of thoughts in my head and sort them out. But painting – well painting is a type of meditation. A way to calm the monkey brain while your hands are busy with patterns and images and your brain is full of visuals. For the two months leading up to the solo gallery show, I put everything else on pause and just paint. I get wanderlust-y, and want to rush but really, what was I rushing towards? Some days painting means having Netflix on while I paint just one layer and spend the rest of the time staring out the window. Other times, more things get accomplished. But I have to remind myself that it is all productive – the thinking and the making. The one goal I set for myself since the start of the pandemic was to be creative everyday, no matter the medium. And that was accomplishment enough.

16. When I was a child, I would watch my mother embroider tiny mirrors onto fabric she would later turn into salwars. I used to love organizing her crafts supplies, and would play with these tiny mirrors, looking at myself in the reflection with one tiny eye. That is what I think of when I super glue the tiny mirrors onto the painted adornment, and see fractured miniature reflections myself looking back at me in these paintings. In the gallery the mirrors on the art reflect tiny sparkles of dancing light on the floor. The Aunties watch you watching them - the mirrors on the pieces reflecting back tiny reflections of what it means to be seen. To be perceived.

17. I hadn’t planned on being their everyday, but somehow, I did. It was only a nine-day long show at the gallery, and it seemed like every day some other friend was stopping by. So I’d go, and sit in the middle of the gallery on a roll-y office chair and just move through the gallery looking at the Aunties as the Aunties eyes followed me. It’s a unique timepass to be surrounded by your creations just waiting for people to come by and see the madness inside your head. It felt like the inside of my head had vomited all over the wall, but it was well-lit and framed. The Aunties looked gorgeous when well lit. The mirrors sparkled and the metallic paints shined. They came alive, anthromorphic art. It was an incredibly intimate experience. I thought I would be able to write in a corner of the gallery, but so many people come through, the open doors an invitation to people just walking by on the street. It’s hard to find a time alone to reflect. Each night when we close the gallery, there is a lingering. Lingering on the steps outside, sitting against the eye wall, sprawled on the floor. Especially on the night we start dismantling the art, I take down the pieces slowly and ceremoniously, but even that was too fast. We finally leave at midnight when the ghost of the space tells us to. The gallery served as a timeless time warp of a timepass that I didn’t want to end.

18. The second to last layer, I paint the lasers coming out of the eyes with brightest opaque neon pink. It leaves pink splatters all over my living room.

19. The timepass of standing in a pool, under an umbrella, staring at the Palm Springs sky and feeling the movement of the water float around you and waiting for the gummy to hit the day after taking down all the art.

20. The timepass of a hike on a rocky cliff which culminated in a sunset meditation through silent disco headphones.

21. The timepass of waiting for nothing and feeling like time wasn’t wasted.

22. “I read your press release. So it was your Aunties that this event happened to?” the older White woman said, smugly. “Excuse me?” I respond, in shock. In all my public materials I had mentioned that the Aunties with Deadly Stare series was inspired by the case of two women being pulled off a plane for staring too hard. I thought it was clear. “It was Aunties, but not my Aunts. The universal Aunties.” The White woman looked at with audacious Whiteness, like I was the one in the wrong.

23. The Auntie Talent Show was the culminating closing event – we had a chai-off, a DJ outside, and all kinds of friends performed in different Auntie ways. Everyone left a little transformed after. At the Auntie Talent Show event, Traci reads the poem about how I got sick, the way she got sick, too. She mentioned how this show was so much more. My real friends knew – the Aunties w/ Deadly Stare wasn’t just art. This was a showcase, a culmination, a magic. I started painting the series because the pandemic started, I lost my job, and got cancer, all in the same month. I kept painting because it was the only thing that would still my mind. I refused to sell my art because it wasn’t about selling, it was about healing. Painting the eyes on repeat turned into this spell churning of protection of body to heal. Sitting in the gallery with all the Aunties up on the walls was like sitting in the center of healing. And I was done making the Aunties – I wanted to move on from this series, my cancer was cut out and gone, and I was finally ready to share all that I had made. It was the timepass of my curing.

24. People kept asking me if my art show was productive, and how many pieces I sold. As if the purpose of the art series was commerce, and not magic.

25. cure (verb): 1. To restore to health. 2. To relieve or rid of something detrimental, such as an illness or bad habit.

26. Paint curing can be defined as the act of paint becoming fully hardened. Whenever you apply paint to a solid material, it goes through a chemical process of bonding to the surface. Paint 'drying' happens when the solvents evaporate from your paint coating, leaving the paint feeling dry to the touch—even though it is not 100% dry. Whilst paint 'curing' happens when your paint coating is completely hardened and fused to the wall.

27. The final layer is the curing. Paint will dry, but the pieces need to dry dry. If you varnish too soon – the acrylic will crack and the paper wrinkle. This process cannot be rushed even if you wished it so. What might seem dry to touch might crack after a week or two. It is only after it is cured can you spray a thin layer of clear varnish to save it as is. The paintings have to be cured – but like human bodies, curing takes time and cannot be rushed.

28. Watching paint dry is the act of being present. It’s unproductive times, unstructured times, and lacking in efficiency. It’s the hospital waiting room of the call. It’s the time sitting at the kitchen table waiting to leave for janaza prayer. It’s intimate conversations while gazing at art and lingering on gallery steps because you don’t know where else you’d rather be. It’s staring at space, clouds, walls. It’s forced presence. To be here.

29. This summer of stasis. It’s curing.

Loved this and will look at my piece with this presence 🩷